EL PASO – Rosa Mejia lives in constant terror of being deported to Mexico. Sicarios, hitmen, hired by a Mexican cartel knocked on Rosa Mejia’s door on a dry, October day. This was the latest in a long line of harassment against Mejia’s family by the cartel. Her brother and sister had been missing since February, and the police had done nothing.

To avoid capture by the Sicarios, Mejia pretended to be someone else, and told them the person they were looking for was at an event in town. As soon as they were gone Mejia fled to seek asylum in the United States.

“When all that happened with my siblings, I decided to leave my home and everything I had. I left my peace and my tranquility to safeguard my life and the lives of the people who fled with me. In that moment I thought it was a good decision because what we wanted was to save our lives. We just didn’t want to be killed,” Mejia said.

Betsaida Lopez, of San Antonio, chants during the march

Mejia shared her story during the El Paso Firme concert to the huddled masses gathered to reject white supremacy. The concert was part of a day-long event held in El Paso during which people from around the country spoke out against white supremacy.

The Border Network for Human Rights (BNHR) collaborated with The Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services (RAICES) to host a day of events in honor of those who lost their lives to racism not only in the El Paso Aug. 3 Walmart shooting, but as far back as the annexation of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and California by the U.S.

Hope began to bleed into El Paso as citizens from across the country stood together in solidarity on Sept. 7 against the hateful rhetoric and actions of white supremacy.

El Paso Firme became a rallying cry through the day, and each time someone would call out “El Paso,” the subsequent “Firme” would get a little louder than before.

Fernando Garcia, executive director of BNHR, believes the normalization of white supremacy rhetoric from President Donald Trump has become a spring of life to those who would hurt others based on their skin color or language.

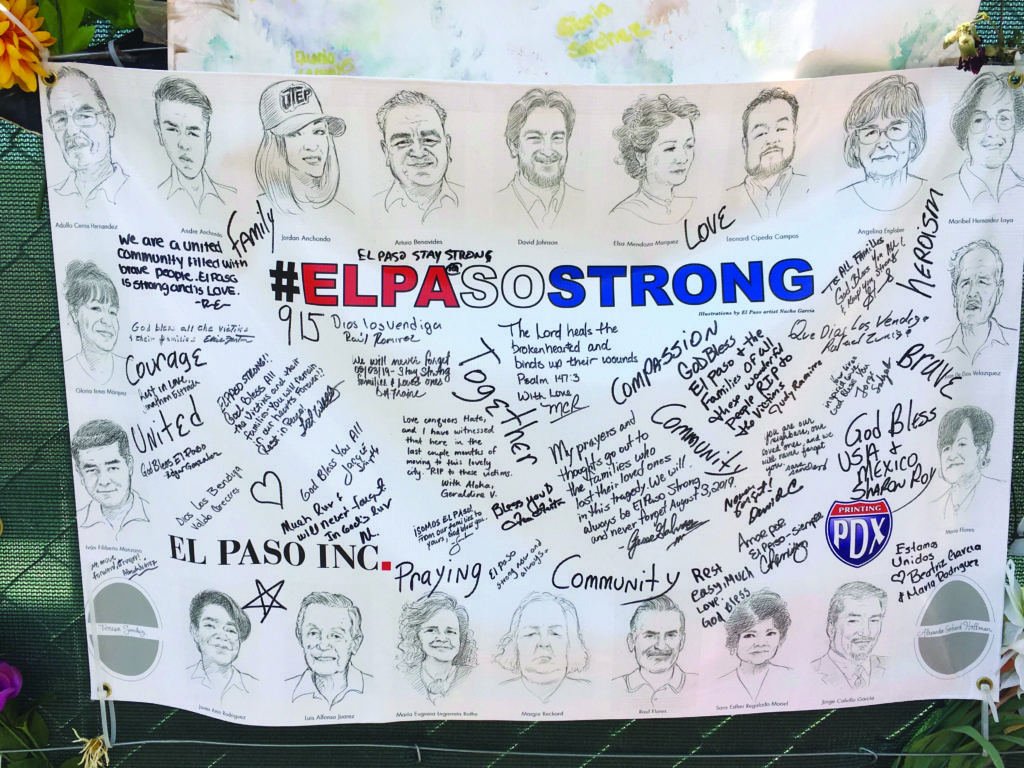

A memorial left for those who lost their lives in the attack.

“We have to say it like it is; we just can’t let it be, President Trump is the one responsible for a lot of the things that are happening. He has come to El Paso to say that us immigrants are a threat, that we are criminals, we are rapists, we are animals and these thoughts contributed to the thoughts of the terrorist who arrived in El Paso to hurt us. El Paso Firme! This is our call to fight, this is our call to take action and reflect, and today we go on looking forward, because we deserve a society free of racism, free of hate and free of white supremacy,” Garcia said to a crowded gym with La Virgen de Guadalupe illuminated in the background.

The BNHR seeks to create a movement to change society that rivals the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s.

“This movement led by immigrants and Latinos is the next civil and human rights movement being constructed,” Garcia said.

Similar to the National Farm Workers Association movement led by Caesar Chavez in the 1960s, the BNHR seeks all the allies it can get.

“What we are fighting for goes beyond nationality. What is relevant is that every community is equal in dignity and rights,” Garcia said. “We need to see each other as human beings, and if we see each other as human beings it is going to be difficult for those differences, whatever they are that makes us so proud, to be the obstacle to relate to each other.”

Greg Abbot, governor of Texas, signed eight executive orders into law right before the mass shooting in Odessa and Midland, Texas, that aimed to stop potential mass shootings, but the word “gun” does not appear in any of them. Chief Advocacy Officer of RAICES Erika Andiola has had enough of politicians dancing around the problem.

People from all over the state have visited the memorial to pay their respects for the 22 victims who were killed.

“It’s not enough, and this is the moment for any politician, any elected official whether you’re Republican or Democrat or any other party to come to the realization that America has a gun problem, that we’ve been having a gun problem,” Andiola said.

“When you have so many guns available for people who are already wanting to hurt others, who have heard President Trump say over and over again that people from other nations, people who look differently, should be kicked out of the country, all this rhetoric is really creating an atmosphere of people who want to attack others.”

While voting is one of the issues BNHR focuses on, members’ goals are much bigger.

“Registering to vote is one thing, and it is very important to say that elections and voting is one very important thing, but not the only thing,” Garcia said. “We need to take the streets, we need to denounce [white supremacy], we need to organize communities. At the end of the day, what sense does it make for people to register to vote, if the options out there don’t reflect their communities or if their communities don’t have the capacity to influence candidates?”

Stephanie Villaneva and her mother Laura Villaneva lighting prayer candles.

Garcia realizes that the issues his, and other, organizations seek to rectify are many in number, but argues that these problems are symptomatic of a systemic failing.

“All of these issues individually make sense for individual fights in local communities, but we cannot ignore anymore that they are a part of the system,” Garcia said.

By refusing to isolate issues by region, these organizations actively accept people like Mejia, whose tribulations are not unique.

Many tears were shed and stories shred during El Paso Firme.

Alone, covered in blood and bruises, a man illegally crossed the U.S.-Mexican border to narrowly escape death. Hunted, beaten and left for dead, Hermelinda Blanco and Carlo Barajas’ son made his way into the U.S. only to end up in a detention center. His tormentors then turned their attention to the couple.

“We went down several streets of Juarez city and they continued to follow us, and that’s when we decided to come in search of political asylum. Since then, we have been here waiting to see what we can resolve,” Blanco said.

Blanco and Barajas, Mejia, the Latino community and the nation are waiting to see how the discrimination by white supremacists is going to be resolved.